It is difficult enough to learn about the removal, often by force, of native children from their families. And about the terrible things done to the children at the institutions of forced assimilation. The remains of thousands of children are being found on the grounds of many of those institutions. The numbers found are rapidly increasing with the use of ground penetrating radar. Indigenous peoples say these findings confirm what they already know. Thousands of children never returned to their families.

The explanation given was the children were being taught how to fit into white culture. It wasn’t until recently that I realized the intentional cruelty was the point. To break the resistance of tribes to removal from their lands. The cruelty worked.

As those institutions were eventually closed, children continued to be removed by state welfare systems. Often to be placed with non-native families.

The era of assimilative U.S. Indian boarding schools started to wane and eventually came to a close after government reports like the Meriam Report (1928) and the Kennedy Report (1969) found mistreatment and abuse to be rampant at the costly institutions. During this time, the federal government shifted its assimilative methods, using the Indian Adoption Project to transfer Native children from their homes and place them directly with white adoptive and foster families.

In full swing in the 1960s and 1970s, the adoption era saw (usually white) social workers deem huge proportions of Native families unfit for children. In fact, by 1978, as many as one-quarter to one-third of children were taken by social workers or other coercive means and either adopted out of the tribe or placed in the non-tribal foster care system. Although the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 (ICWA) was designed to address this form of cultural genocide, Native families continue to face very high levels of child removal. For example, in Alaska, where Native children make up 20% of the general child population, they represent 50.9% of children in Foster Care. In Nebraska, Native children make up just 1% of the general child population, but 9% of the children in foster care. (National Indian Child Welfare Association and The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2007).

In 1978, the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) was passed to re-establish tribal authority over Native children, due to high rates of state removal of children. In spite of ICWA’s passing, Native children were placed into foster care at high rates in Maine. Concerns about the contemporary relationship between the state welfare system and the tribes, as well as the lasting effects of foster care trauma on tribal communities, brought about the Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the first Truth and Reconciliation Commission between Native peoples and child welfare.

The Maine Wabanaki-State TRC: Healing from historic trauma to create a better future By Genevieve Beck-Roe, American Friends Service Committee, Jan 27, 2016

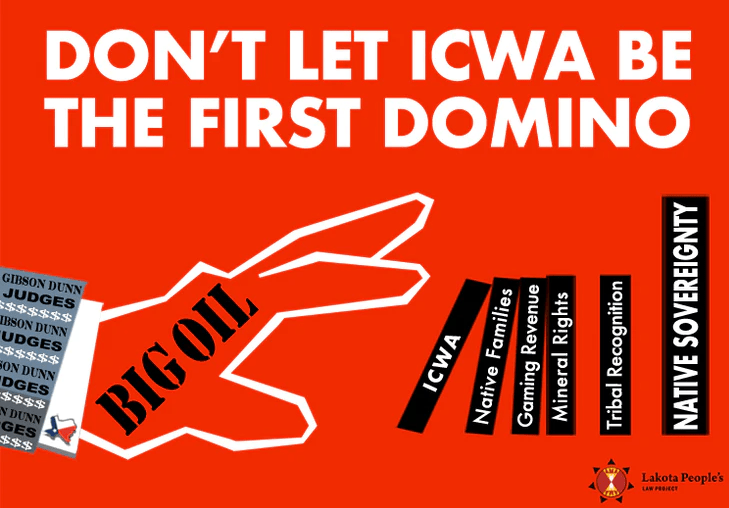

Native children and U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland are under legal attack in Brackeen v. Haaland. The powerful people behind the lawsuit include both Big Oil and the State of Texas. If their attempt to have a conservative-majority Supreme Court overturn the Indian Child Welfare Act is successful, the door will be open to the total elimination of tribal sovereignty. Take action now to stop this horrific attack on Native rights! (see petition below).

Lakota People’s Law Project

Texas, Big Oil Lawyers Target Native Children in a Bid to End Tribal Sovereignty

The Threat Summarized

If the Supreme Court overturns the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) — a federal law that keeps Native children with Native families — tribal sovereignty could soon be a thing of the past in the U.S. Should the justices rule in the plaintiffs’ favor in the case of Brackeen v. Haaland, we could quickly see a return to blatant, pre-1978 genocidal practices — when Native babies were legally stripped of their families, culture, and identities.

It’s critical that every one of us take immediate action. Before you do anything else today, sign our petition telling President Biden and the Department of Justice to defend ICWA, Secretary Haaland, and tribal sovereignty with every available means.

In this landmark case, the Brackeens — the white, adoptive parents of a Diné child in Texas — seek to overturn ICWA by claiming reverse racism. Joined by co-defendants including the states of Texas, Ohio, Louisiana, and Indiana, they’re being represented pro bono by Gibson Dunn, a high-powered law firm which also counts oil companies Energy Transfer and Enbridge, responsible for the Dakota Access and Line 3 pipelines, among its clients. This lawsuit is the latest attempt by pro-fossil fuel forces to eliminate federal oversight of racist state policies, continue the centuries-long genocide of America’s Native populations, and make outrageous sums of money for energy magnates, gaming speculators, and fossil fuel lawyers. The story below may seem unbelievable, but it is 100 percent true.

Key Points to Take Away

- Big Oil’s lawyers, Texas, and three other states with very few Native inhabitants are attacking the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA).

- The Texas Attorney General is asking the Supreme Court to declare ICWA unconstitutional.

- The Plaintiffs argue that tribal affiliations should be considered racial, rather than political, designations.

- Overturning ICWA could be the first legal domino in a broader attack on tribal rights and sovereignty.

The Indian Child Welfare Act Protects Native Kids, Cultures, and Sovereignty

The Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) is the federal law that prioritizes Native care for Native children, which is critical to maintaining cultural connections, family ties, and kinship practices that have been intact for thousands of years. ICWA, signed into law in 1978, was conceived as a means of slowing the genocidal policies enacted by the United States and Canada, which included the forced placement of Indigenous children in Indian boarding schools for more than a century.

These schools were cruel institutions designed to enact genocide by separating the children from their cultural identities and severing ties with their families and communities. Thousands of Native and First Nations children died at these schools, where physical, mental, and sexual abuse were commonplace. After the era of boarding schools, during the Sixties Scoop, it became common practice for child welfare workers — hiding behind state law — to kidnap Native children and place them with white, Christian families as adoptees. This lasted well past the 1960s, and ICWA was ultimately passed to protect Native children and keep them with their kin.

Today, the State of Texas (among other plaintiffs) is suing the federal government in an attempt to overturn ICWA. If the plaintiffs are successful, this case will strike down the federal law that prioritizes Native care for Native children. But that’s not even the worst of it. The case would also open a door for the destruction of tribal sovereignty in the United States. The case — Brackeen v. Haaland — is slated to go before a conservative Supreme Court soon, should the justices accept it. It specifically names the defendant as U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland — a Laguna Pueblo woman and the first Native person to hold a Cabinet secretary position in U.S. history.

The plaintiffs are essentially alleging racism against white people, arguing that ICWA violates the U.S. Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause. Tribal nations — backed by a prior Supreme Court decision — say that Native status is not a racial designation, but a political one.

This case poses an extreme and imminent danger to Native Peoples across the U.S. If the high court accepts the plaintiffs’ argument that tribal political designations should not count in custody cases, “Native” and “Indian” designations could then be dissolved entirely. That decision would position ICWA as the first domino to fall, potentially leading to the erosion — or total erasure — of Native rights in the only homelands Indigenous North Americans have ever known.

Lakota People’s Law Project

https://lakotalaw.org/news/2021-09-17/icwa-sovereignty

Petition to protect the Indian Child Welfare Act

Dear President Biden and attorneys for the Department of Justice,

As the Supreme Court decides on whether to render judgment in the case of Brackeen v. Haaland, I write today to ask you to do everything in your power to protect the Indian Child Welfare Act and defend Secretary Deb Haaland. We need strong federal protection of Native families and tribal sovereignty.

Please file every available motion, prepare every legal argument judiciously, and do everything else you can to stop this attack on tribal citizens. The plaintiffs will not be easily stopped. Should the Supreme Court accept this case and validate the plaintiffs’ argument that tribes do not have the power to place their own enrolled children in tribal kinship care, we will have crossed a rubicon into dangerous legal territory that could ultimately lead to the disbanding of tribal nations — and the loss of tribal lands, gaming revenues, and mineral rights.

It’s no coincidence that the same attorneys — Gibson Dunn — representing the plaintiffs in this case also have deep ties to fossil fuel interests such as Enbridge and TC Energy (the oil conglomerates responsible for attacking tribal interests through the Line 3 and Dakota Access pipelines, respectively).

The Indigenous peoples of this land have always deserved better. The few gains made over centuries littered with oppression, and in the face of overwhelming systemic racism, must not be lost now. Please fight hard to protect original Americans. Please do everything possible to stop this attack on children, families, and sovereignty.

You can sign this petition here:

https://action.lakotalaw.org/action/protect-icwa