It has taken a while to adjust to thinking of abolition as the elimination of prisons instead of the historical context of abolition of the institution of enslavement. Not surprisingly the concept of prison abolition comes up in any discussion of capitalism and building a just future. Police are the enforcers of capitalism.

I am part of a new group of Friends who are interested in abolishing police and prisons called the Quakers for Abolition Network (QAN).

The following is from an article Jed Walsh and Mackenzie Barton-Rowledge, who helped start QAN, wrote for Western Friend.

Mackenzie: Let’s start with: What does being a police and prison abolitionist mean to you?

Jed: The way I think about abolition is first, rejecting the idea that anyone belongs in prison and that police make us safe. The second, and larger, part of abolition is the process of figuring out how to build a society that doesn’t require police or prisons.

M: Yes! The next layer of complexity, in my opinion, is looking at systems of control and oppression. Who ends up in jail and prison? Under what circumstances do the police use violence?

As you start exploring these questions, it becomes painfully clear that police and prisons exist to maintain the white supremacist, heteronormative, capitalist status quo.

Abolish the Police by Mackenzie Barton-Rowledge and Jed Walsh, Western Friend, November December, 2020

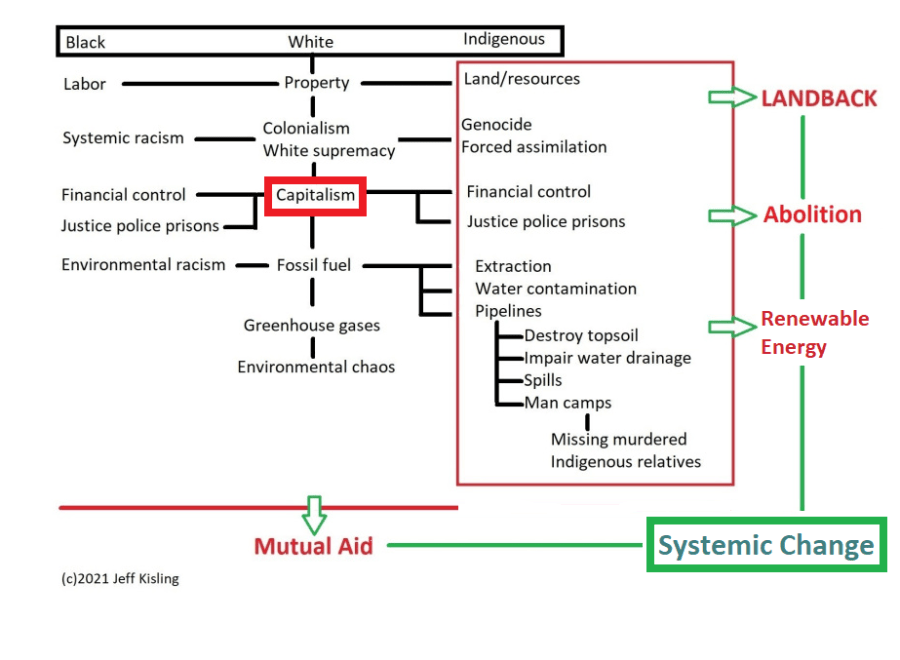

This diagram shows abolition, along with LANDBACK and Mutual Aid, as pieces of changes to transition away from systems of capitalism and white supremacy.

I’ve been reading The Red Deal by the Red Nation, which is about empowering Indigenous peoples, in part to help guide us through environmental chaos. What follows are some interesting perspectives on prison abolition.

Austerity is enforced scarcity. The neoliberal policy of the last forty years has been a tax strike of the super wealthy, who have refused to pay their share of taxes and have locked away the world’s wealth in tax havens and offshore accounts. These are resources that should go towards providing services—education, housing, healthcare, public transportation, infrastructure, and environmental restoration—to those who actually produce the wealth: the Indigenous, Black, migrants, women, and children who are the workers of the world. This strike is worth crushing quickly and with prejudice. Direct action alone won’t reallocate wealth if it is not backed by popular mass movements and enforced by state apparatuses wrested away from the elite and powerful.

Prison abolition and an end to border imperialism are key aspects of the Red Deal, for good reason. The GND calls for the creation of millions of “green” jobs, as well as a policy of “just transition” for poor and working-class families and communities that currently depend on resource extraction for basic income and needs, and which will suffer greatly when the extractive industry is shut down. In the United States today, however, about seventy million people—nearly one-third of adults—have some kind of criminal conviction—whether or not they’ve served time—that prevents them from holding certain kinds of jobs. If we add this number of people to the approximately eight million undocumented migrants, the sum is about half the US workforce, two-thirds of whom are not white. Half of the workforce faces employment discrimination because of mass criminalization and incarceration.

The terrorization of Black, Indigenous, Brown, migrant, and poor communities by border enforcement agencies and the police drives down wages and disciplines poor people—whether or not they are working—by keeping them in a state of perpetual uncertainty and precarity. As extreme weather and imperialist interventions continue to fuel migration, especially from Central America, the policies of punishment—such as walls, detention camps, and increased border security—continue to feed capital with cheap, throwaway lives. The question of citizenship—colonizing settler nations have no right to say who does and doesn’t belong—is something that will have to be thoroughly challenged as a “legal” privilege to life chances. Equitable access to employment and social care must break down imperial borders, not reproduce them.

The Red Deal by The Red Nation (pp. 22-23). Common Notions. Kindle Edition.

Calls for abolition of the prison system have expanded in the wake of widespread police violence. Abolition is part of the work of our Mutual Aid community.

Prison abolition and an end to border imperialism are key aspects of the Red Deal

The Red Nation

This same war of conquest is currently using the mass incarceration machine to instill fear in the populace, warehouse cheap labor, and destabilize communities that dare to defy a system that would rather see you dead than noncompliant. This is the same war where it’s soldiers will kill a black or brown body, basically instinctively, because our very existence reminds them of all that they have stolen and the possibility of a revolution that can create a new world where conquest is a shameful memory.

What we have is each other. We can and need to take care of each other. We may have limited power on the political stage, a stage they built, but we have the power of numbers.

Those numbers represent unlimited amounts of talents and skills each community can utilize to replace the systems that fail us. The recent past shows us that mutual aid is not only a tool of survival, but also a tool of revolution. The more we take care of each other, the less they can fracture a community with their ways of war.

Ronnie James, The Police State and Why We Must Resist

Policing in the United States is a force of racist violence that is entangled at the core of the capitalist system. As Robin D.G. Kelley pointed out on Intercepted With Jeremy Scahill, capitalism and racism are not distinct from one another: “If you think of capitalism as racial capitalism, then the outcome is you cannot eliminate capitalism, overthrow it, without the complete destruction of white supremacy, of the racial regime under which it’s built.”

Police in the United States act with impunity in targeted neighborhoods, public schools, college campuses, hospitals, and almost every other public sphere. Not only do the police view protesters, Black and Indigenous people, and undocumented immigrants as antagonists to be controlled, they are also armed with military-grade weapons. This police militarization is a process that dates at least as far back as President Lyndon Johnson when he initiated the 1965 Law Enforcement Assistance Act, which supplied local police forces with weapons used in the Vietnam War. The public is now regarded as dangerous and suspect; moreover, as the police are given more military technologies and weapons of war, a culture of punishment, resentment and racism intensifies as Black people, in particular, are viewed as a threat to law and order. Unfortunately, employing militarized responses to routine police practices has become normalized. One consequence is that the federal government has continued to arm the police through the Defense Logistics Agency’s 1033 Program, which allows the Defense Department to transfer military equipment free of charge to local enforcement agencies.

TO END RACIAL CAPITALISM, WE WILL NEED TO TAKE ON POLICING By Henry A. Giroux, Truthout, June 20, 2021