Sometimes when people compliment a photo I’ve taken, I’ll say the Creator deserves the credit. Then they would often say I had a role in how the beauty was captured.

I usually wouldn’t say anything further, but there is much more to my relationship with the Spirit and photography.

Years ago I began to noticed I was having conversations with the Creator. ‘I love the majesty of these mountains’. ‘Wow, this is a beautiful flower you created’. ‘These mountains humble me’. ‘You know what I’m trying to do here. Could you help me out?’. I asked that last question often, because I intentionally challenge myself and the Spirit to capture difficult images.

There is a connection between the image, the camera, my eyes, the Spirit and the image. A full circle. The Spirit refining how the image is seen.

As I walk with my camera, my eyes scan from side to side, up and down. But very often my attention is drawn by a force beyond me, or within me. By the Spirit. Or Inner Light, which is an interesting juxtaposition with light and photography. I walk slowly, in silence, so I can hear where I should look. If there is a complex scene before me, I stop and wait. Usually, after some time, the image within the scene will emerge. These are sacred times. In some ways making me much more present in the moment. And in other ways taking me to a different space.

There is a connection between the image, the camera, my eyes, the Spirit and the image. A full circle. The Spirit refining how the image is seen.

Prior to digital photography I developed film negatives and printed photos in darkrooms, first as a student at Scattergood Friends School and then as yearbook staff at Earlham College. Doing darkroom work was very popular with the kids I worked with as part of the Friends Volunteer Service Mission in the early 1970’s. I can still see their expressions (via the orange darkroom light) as the images magically formed on the paper in the developer solution.

The process of developing the negatives and prints is technically challenging. And rolls of film would have room for a limited number of photos so you had to make each shot count.

Prior to the advent of digital photography I don’t believe there was automatic control of focus or exposure settings for shutter speed and lens aperture. I think some cameras had built in light meters.

Digital photography was revolutionary. Besides automating focus and exposure, you can actually preview how the photo will look. Eliminating the problems of the darkroom, and allowing as many images as the memory card could hold. Which could be erased and used over and over again. I like the sustainability that reuse represents. I was bothered by all the silver that was used to make the emulsion for photographic film.

The camera became an amazing teacher, giving me the freedom to take as many shots, with as many variations as I wanted. The last time I visited the mountains I wasn’t sure if I would return. So I took 1,093 photos during those four days, most of which you can see here: Colorado 2017.

Although I was raised on farms and had a deep connection with nature, being in the Rocky Mountains was spiritually transformative. Changed my life in many ways. I’m so blessed our family would often spend summer vacations camping in Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado.

I felt closer to God when we were deep in the quiet of the forests or high on the mountainside. Having grown up in Quaker communities, I was used to worshiping in silence so we can hear the whisper of the Spirit. Being enveloped in the silence of the mountains was a natural relation to Quaker worship. Or as I think of this now, Quaker worship is a natural extension of the silence of the mountains. Silence in the sense of quiet, but at times loud with the voice of the Spirit.

Quakers often refer to our business meetings as meeting for worship with attention to business. Emphasizing the spiritual basis of what would be discussed. I began to think of the quiet I moved through with my camera, even in the city, as meeting for worship with attention to photography.

On those rare occasions when I didn’t have my camera with me I would still be recording images in my head. Once my good friend Diop Adisa and I were talking about photography. I was surprised to learn he also took mental photos when without a camera. We called that Zen photography. I remember how we laughed at those shared observations.

This is a photo I took of Long’s Peak in the early 1970’s. I printed it in the darkroom and kept it near me, a reminder of the mountains. Looking forward to returning.

When I moved to Indianapolis in 1971, I was just shocked by the clouds of noxious smog. That was before catalytic converters. I could not, and still can not understand how people could continue to drive when they were destroying our environment. Even today with “Code Red” reports on our environment people don’t make the connection to the years of fossil fuel emissions from automobiles. Or at least don’t feel a sense of accountability themselves. Can not conceive of life without a car. It is too late for that. I can not bear to hear the clamor to fix Mother Earth now, when what needed to be done decades ago was completely ignored.

I kept seeing an image of my beloved mountains obscured by smog. I would look at the photo above, and imagine not being able to see that in the future. That was incomprehensible and devastating, and led me to refuse to have a car for the rest of my life.

Although not having a car made many things more difficult there were many positive consequences. Besides turning me into an avid runner, for transportation and enjoyment, perhaps the most significant was related to my photography and the spiritual aspects of that.

I selected places where I lived to be within three miles of the hospital where I worked. Although when I first began running home from work I lived seven miles away. I’d either take a bus, or walk to work so a shower wouldn’t be needed. Then run home. Wearing scrubs at the hospital was great because I didn’t have to bring clothes that were bulky or needed not to be wrinkled. When I moved from one apartment to another, the criteria included being on a bus route and within walking distance of a grocery store and the hospital.

Walking or running outdoors everyday allowed me to look more closely and see the beauty around me. As I became more aware of my surroundings I began to take my camera with me every day. And not just when going to work. I had to start out earlier than usual to compensate for the time I spent looking for and taking photos. I lose track of time.

At first people would comment on the constant presence of my camera. But it wasn’t long before people would instead ask where my camera was if I did not have it with me.

I admired photographers like Ansel Adams, not only for their amazing images, but how they used their skill to try to make others see the importance of protecting these beautiful lands.

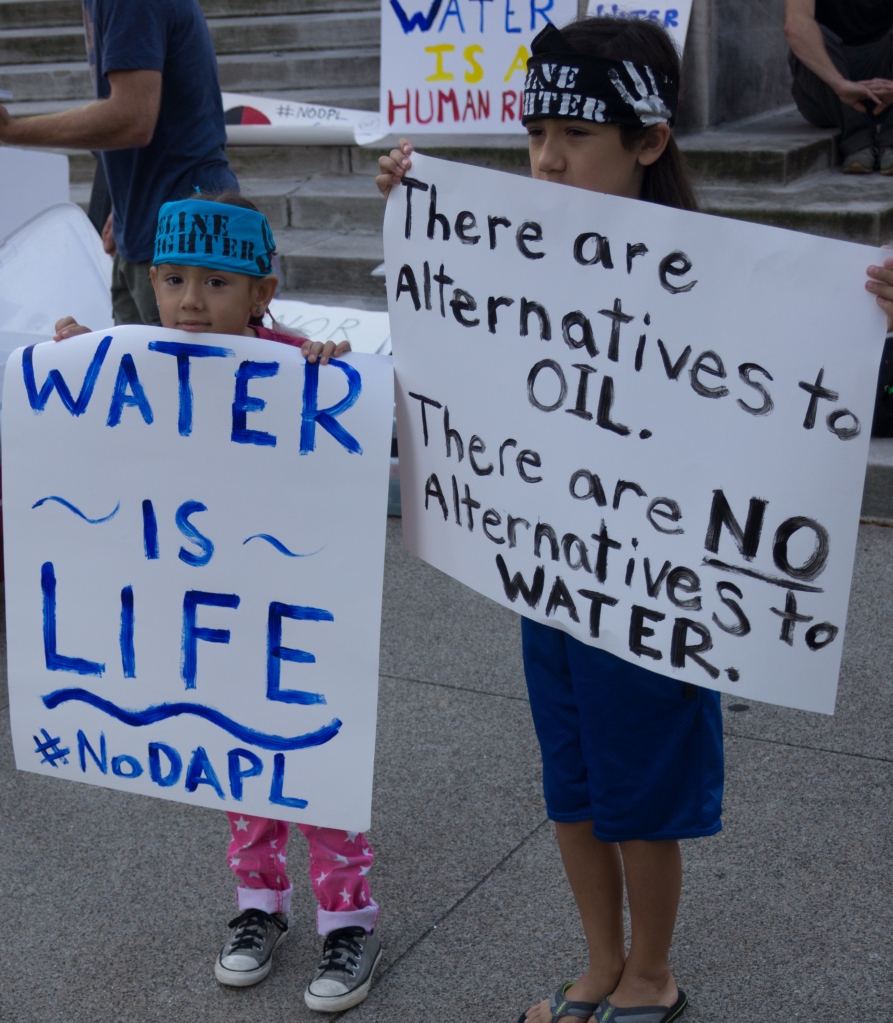

I never thought I’d see the vast destruction of nature from air, water and soil pollution. From oil pipeline construction and spills. Millions of acres laid to waste from mining tar sands. The intentional destruction of vast forests. The death of coral reefs. The removal of entire mountaintops! The severe, ongoing drought of the entire West. Devastating fires and violent storms. Fires in Rocky Mountain National Park. Experience temperatures from heat domes which are reaching the point of being not survivable.

Or witness my long ago nightmare of mountain beauty obscured. Now not by smog, but by the smoke from huge and ferocious wildfires hundreds of miles away.

I never thought my images might be records of the beauty of Mother Earth as it was before all this destruction. Beauty that will never be restored. Beauty of all kinds rapidly disappearing. I’ve written profusely about all these things. But I get the sense that my photos have more of an impact. Speaking for Mother Earth in ways words can not. Thinking perhaps I should just stop writing and capture and share images instead. Before more beauty disappears.

to save a wilderness… one must reach deep into one’s heart and find what is there, then speak it plainly and without shame.

Robert Leonard reid

How could we convince lawmakers to pass laws to protect wilderness? (Barry) Lopez argued that wilderness activists will never achieve the success they seek until they can go before a panel of legislators and testify that a certain river or butterfly or mountain or tree must be saved, not because of its economic importance, not because it has recreational or historical or scientific value, but because it is so beautiful.

I left the room a changed person, one who suddenly knew exactly what he wanted to do and how to do it. I had known that love is a powerful weapon, but until that moment I had not understood how to use it. What I learned on that long-ago evening, and what I have counted on ever since, is that to save a wilderness, or to be a writer or a cab driver or a homemaker—to live one’s life—one must reach deep into one’s heart and find what is there, then speak it plainly and without shame.

Reid, Robert Leonard. Because It Is So Beautiful: Unraveling the Mystique of the American West . Counterpoint. Kindle Edition